Current Electricity

Electric Current And Ohm’s Law Temperature Coefficient of Resistance

Temperature Definition

The temperature coefficient of resistance is defined as the change in resistance of the conductor per unit resistance at 0°C for a 1°C rise in temperature.

Suppose, the resistance of a conductor at 0°C = R0 and its resistance at t°C = Rt

Therefore, according to the definition, the temperature coefficient of resistance of the conductor

⇒ \(\alpha=\frac{\text { change in resistance }}{\text { resistance at } 0^{\circ} \mathrm{C} \times \text { change in temperature }}\)

or, \(\alpha=\frac{R_t-R_0}{R_0 t}\)….(1)

The value of α is different for different substances.

Unit:

Unit of \(\alpha=\frac{\text { unit of }\left(R_t-R_0\right)}{\text { unit of } R_0 \times \text { unit of } t}=\frac{\text { ohm }}{\mathrm{ohm} \times{ }^{\circ} \mathrm{C}}\)

= \(=\frac{1}{{ }^{\circ} \mathrm{C}} \text { i.e., per degree Celsius or } \cdot{ }^{\circ} \mathrm{C}^{-1}\)

The temperature coefficient of resistance of copper is 0.00425 °C-1 means that if the resistance of a conductor of copper at 0°C is 1Ω, for 1°C rise in temperature, the increase in its resistance will be 0.00425 Ω.

Temperature Coefficient Of Resistance Class 12 Notes

Positive and negative α:

In the case of a metallic conductor its resistance Increases with the rise In temperature,

Example:

In the case of copper mentioned above, α = +0.00425 C-1. On the other hand, the resistance of an electrolyte, or a gas maintained at a low pressure or semiconductor decreases with the rise of temperature. So, In these cases Is negative.

Accurate measurement:

From equation (1) we get,

Rt – R0 = R0αt

or, Rt = R0 (1 + αt)………………………………….(2)

In case of metallic conductors if the change in temperature Is not too high then the coefficient remains constant. It means that resistance Increases at a uniform rate with the rise in temperature.

Hut if the change In temperature is very high, then the temperature coefficient of resistance does not remain constant and another constant (β) is required in addition to α. Finally, the modified form of the equation (2) is

Rt = R0 (l + αl + βt2)…(3)

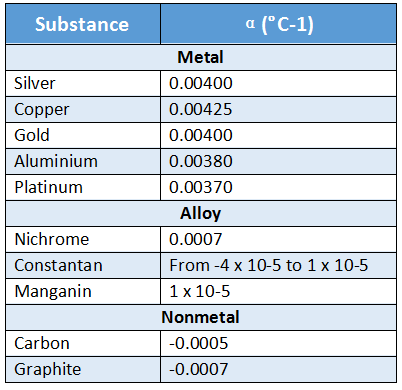

Values of α for different substances:

A table showing the values of the temperature coefficient of resistance of a few substances is given below, taking β = 0.

From the above table, it will be noticed that:

1. The value of a is greater for metals than for alloys. Therefore, metals show more change in resistance titan alloys, when they are heated.

This is the basic reason why alloys are used in resistance boxes and metals are used in the construction of resistance thermometers.

2. In substances like carbon, graphite or constantan, α Is negative i.e., their resistance decreases with theriseintemperature

Conventional rule:

In the laboratory, to determine the value of a it is not necessary to determine the resistance of the metallic conductor at 0°C. If R1 and R2 be the resistances of the conductor at t1°C and t2°C respectively, then,

⇒ \(R_1=R_0\left(1+\alpha t_1\right) \text { and } R_2=R_0\left(1+\alpha t_2\right)\)

So, \(\frac{R_1}{R_2}=\frac{1+\alpha t_1}{1+\alpha t_2} \text { or, } R_1\left(1+\alpha t_2\right)=R_2\left(1+\alpha t_1\right)\)

or, \(\alpha\left(R_1 t_2-R_2 t_1\right)=R_2-R_1 \quad \text { or, } \alpha=\frac{R_2-R_1}{R_1 t_2-R_2 t_1}\)

This relation is used in the laboratory to determine α of a substance.

Chango of resistivity with temperature:

Let us suppose that resistance, resistivity, length, and cross-sectional area of a conductor at 0°C are R0, \(\rho\)0, l0, and A0 respectively, and the corresponding values at t°C are R, p,l and A.

Now, let the temperature coefficient of resistance of the material of the conductor = a; coefficient of linear expansion = α’

Coefficient of superficial expansion = β = 2α’

So, \(R=R_0(1+\alpha t), l=l_0\left(1+\alpha^{\prime} t\right), A=A_0\left(1+2 \alpha^{\prime} t\right)\)

Again, \(\rho_0=\frac{R_0 A_0}{l_0} \text { and } \rho=\frac{R A}{l}\)

∴ \(\frac{\rho}{\rho_0}=\frac{R}{R_0} \cdot \frac{A}{A_0} \cdot \frac{l_0}{l}\)

⇒ \(\frac{(1+\alpha t)\left(1+2 \alpha^{\prime} t\right)}{1+\alpha^{\prime} t} \approx(1+\alpha t)\left(1+\alpha^{\prime} t\right)\) [∵ α’ is very small]

∴ \(\rho=\rho_0(1+\alpha t)\left(1+\alpha^{\prime} t\right)\)

So, the resistivity of the material of a conductor increases with the rise in temperature.

Class 12 Physics Important Questions On Ohm’s Law And Resistance

Current Electricity

Electric Current and Ohm’s Law Temperature Coefficient of Resistance Numerical Examples

Example 1. The temperature coefficient of resistance of copper is 42.5 x 10-4 °C-1. The resistance of a coll of copper at 30°C is 8 IT. What is its resistance at 100°C?

Solution:

⇒ \(R=R_0(1+\alpha t)=R_0 \alpha\left(\frac{1}{\alpha}+t\right)\)

⇒ \(\text { At } 30^{\circ} \mathrm{C}, R_{30}=R_0 \alpha\left(\frac{1}{\alpha}+30\right)\)

⇒ \(\text { At } 100^{\circ} \mathrm{C}, R_{100}=R_0 \alpha\left(\frac{1}{\alpha}+100\right)\)

So, \(\frac{R_{100}}{R_{30}}=\frac{\frac{1}{\alpha}+100}{\frac{1}{\alpha}+30}\)

Now, \(\frac{1}{\alpha}=\frac{1}{42.5 \times 10^{-4}}=\frac{10000}{42.5}=235.3\)

So, \(R_{100}=R_{30} \times \frac{235.3+100}{235.3+30}=8 \times \frac{335.3}{265.3}=10.1 \Omega\)

Resistance at 100°C \(R_{100}=R_{30} \times \frac{235.3+100}{235.3+30}=8 \times \frac{335.3}{265.3}=10.1 \Omega\)

Example 2. If \(\rho\) is the resistivity at temperature T, then the temperature coefficient of reactivity is defined as \(\alpha=\frac{1}{\rho} \frac{d \rho}{d T}\), which is a constant physical quantity for a given metal. Show that \(\rho=\rho_0 e^{\alpha\left(T-T_0\right)}\), where \(\rho_0\) = resistivity at temperature T0.

Solution:

It is given that temperature coefficient of resistivity,

⇒ \(\alpha=\frac{1}{\rho} \frac{d \rho}{d T} \quad \text { or, } \frac{d \rho}{\rho}: x \cdot d T\)

Integrating both sides, we get

\(\int \frac{d \rho}{\rho}=\int \alpha \cdot d T\)or, \(\log _k \rho=\alpha T+k\)…(1)

where k = integration constant.

When T = T0, \(\rho=\rho_0\)

∴ \(k=\log _e \rho_0-\alpha T_0\)

Putting k in equation (1), \(\log _e \rho=\alpha T+\log _e \rho_0-\alpha T_0\)

or, \(\log _e \frac{\rho}{\rho_0}=\alpha\left(T-T_0\right) \quad \text { or, } \frac{\rho}{\rho_0}=e^{\alpha\left(T-T_0\right)}\)

∴ \(\rho=\rho_0 e^{\alpha\left(T-T_0\right)}\)