WBBSE Chapter 2 Behaviour Of Gases Pressure Exerted By A Gas And Its Volume

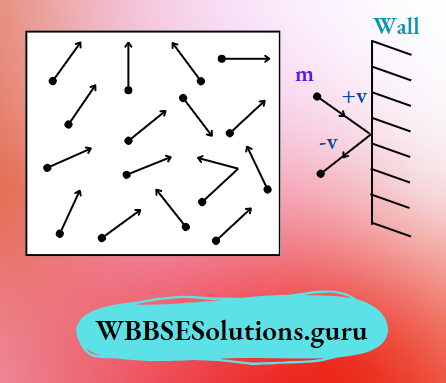

Pressure: Gases are made up of a large number of tiny particles (called molecules) which are moving randomly in all possible directions at all possible speeds within the available space of the container.

As a result, gas molecules collide with the inner walls of the container. After a collision, gas molecules bounce off and their direction of motion changes.

This creates a change in momentum of the gas molecules and produces a force \(\left(\mathrm{F}=\frac{m v-m u}{t}\right)\) normally on the wall.

Wbbse Class 10 Physical Science Notes

WBBSE Notes For Class 10 Physical Science And Environment

The pressure of a gas is defined as how much force is exerted normally per unit area on the wall of the container.

If a force F is applied on a surface of area A then the pressure of the gas, p=F/A. Volume Gases have neither a fixed shape nor a fixed volume.

Gases occupy the available volume of the container in which it is kept, whether the container is big or small.

So, the volume of gas = the volume of the container available for the free movement of gas molecules.

Units of pressure and volume: In the CGS and SI systems, units of force are respectively dyn and N and units of area are respectively cm² and m².

So, the unit of pressure in the CGS unit is dyn/cm² and in the Sl system, it is N/m²or pascal (Pa). (1 Pa = 10 dyn/cm²).

A commonly used unit of pressure is ‘atm’ (atmospheric pressure).

Wbbse Class 10 Physical Science Notes

1 atm =1.01325 × 105 Pa = 101-325 KPa

= 760 mm of Hg = 760 torr = 76 cm of Hg= 1.01325 bar.

And, in CGS and SI systems, units of volume (V) are respectively cm³ and m³. Another commonly used unit of volume is the litre (symbol L) or dm³.

1 m³ = 1000 L = 1000 dm³

As 1L = 1 dm³ and IL 1000 mL = 1000 cm³ so,

1 m³ 106 cm³ 106 mL 109 mm³.

Wbbse Class 10 Physical Science Notes

WBBSE Chapter 2 Behaviour Of Gases Measurement Of Pressure Exerted By A Gas

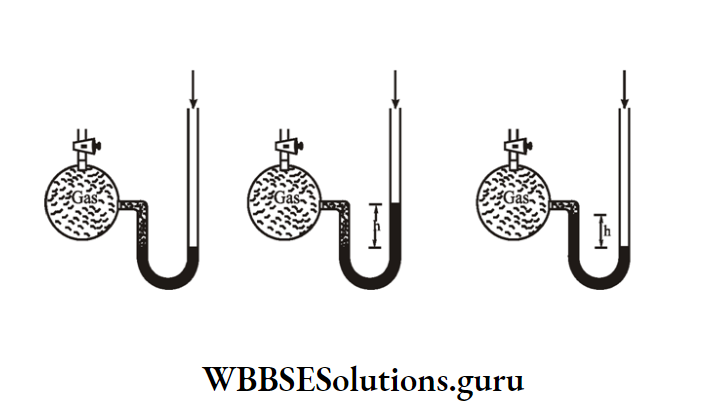

You know that a barometer is used to measure atmospheric pressure. But to measure the pressure of an enclosed gas, we use an instrument known as a manometer or pressure gauge.

Manometer is a U-shaped tube whose one limb is short and another is long. Little mercury is poured into the U-tube.

Under normal conditions, when the stopcock is closed, in two limbs mercury level remains at the same height.

Now a container containing the gas is connected to the short limb. As a result, the gas inside the container exerts pressure on the mercury in the short limb.

Here two different cases may arise:

Wbbse Class 10 Physical Science Notes

Case 1: When the pressure of the gas is more than the atmospheric pressure then the mercury level in the long limb will go higher than in the short limb.

The difference in height of mercury level in two limbs is measured. Suppose this height is ‘h,’ when atmospheric pressure obtained from the barometer is ‘po’.

Since at the same horizontal levels inside the liquid (at points A and B) pressures are the same PA (pressure at point A) = Pg (pressure at point B)

⇒ \(p_{\text {gas }} \text { (pressure of gas) }=p_0+\rho g h_1\)

⇒ \(\text { [where } p_{\mathrm{B}}=p_0+\rho g h_1 ; \rho \rightarrow \text { density of mercury, } g \rightarrow \text { acceleration due to gravity] }\)

Case 2: When the pressure of a gas is less than atmospheric pressure than the mercury level in the short limb.

will go higher than in the long limbs. Suppose ‘h’ be the difference in height of mercury levels in two limbs.

Since at same horizontal levels inside liquid at points C and D, pressures are same so that Pc (pressure at point C) = PD (pressure at point D)

⇒ \(p_{\text {gas }}+\rho g h_2 \quad=p_0\)

⇒ \(p_{\text {gas }} \text { (pressure of gas) }=p_0-\rho g h_2\)

WBBSE Chapter 2 Behaviour Of Gases Boyle’s Law

Basically, the physical behaviour of a given amount of gas (mass or a number of moles fixed) depends on three factors, namely, pressure (p), volume (V) and temperature (T).

Keeping one-factor constant out of these three, we will see how the remaining two factors depend upon one another in studying some important generalisations of Gas Laws.

In 1662 Irish scientist Robert Boyle extensively studied the relationship between the pressure of a gas and the volume it occupies. He made experiments with an air pump designed by his assistant Robert Hooke.

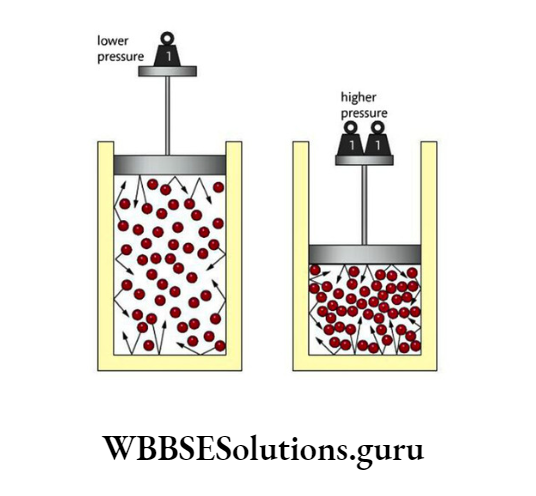

Boyle observed that whenever the pressure of a gas is changed, its volume also changes. As pressure is increased twice, volume decreases to half and as pressure increases to 4 times, volume decreases one-fourth and vice-versa.

In his experiment, he took a fixed mass of gas at a constant temperature. Based on these observations, he discovered a gas law that is known as Boyle’s law.

Wbbse Class 10 Physical Science Notes

Boyle’s law: At a constant temperature, for a given mass of gas, the pressure exerted by the gas is inversely proportional to the volume it occupies.

Here ‘inversely proportional relation’ means that as the pressure goes up, its volume goes down and as the volume goes up, its pressure goes down.

The mathematical expression of Boyle’s law:

For a fixed mass of gas at a constant temperature if V be the volume and p is the corresponding pressure then according to Boyle’s law

⇒ \(V \propto \frac{1}{p} \text { (at constant temperature) or, } V=\frac{k}{p} \text { or, } p V=k\)

where k is a constant of proportionality whose value depends on the temperature and mass of the gas concerned.

The relation “pV=K” explains that the values of p and V can change in such a way that the product p and V always remain the same, provided temperature and mass are kept constant.

If V1 be the initial volume occupied by a gas at initial pressure p1 then according to Boyle’s law: P1V1 = k. Let’s assume that the final volume of the same quantity of gas is V2 at final pressure P2, then P2V2 = k. Now, relate these initial and final conditions :

⇒ \(p_1 V_1=k \text { (constant) }=p_2 V_2 \Rightarrow p_1 V_1=p_2 V_2\)

Wbbse Class 10 Physical Science Notes

1. p vs V graph mathematical form of Boyle’s law is \(p \times \frac{1}{V} \Rightarrow p V=K\) this relation is similar to \(y \propto \frac{1}{x} \Rightarrow y x=c\)

Along the Y-axis, then the nature of the graph is like a rectangular hyperbola.

The graph shows that if V is very high then p is very low and if V is very low then p is very high such that pV = constant provided temperature remains constant at all points.

This type of graph at constant temperature is called an isotherm. (iso = same, therm temperature).

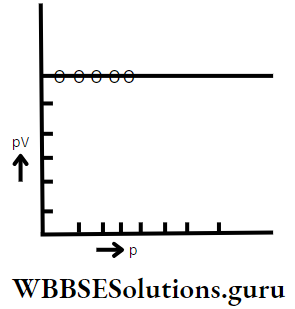

2. pV vs p graph:

The mathematical form of Boyle’s law is pV = K. If p is changed then the corresponding value of V also changes but the value of product pV remains constant.

So if p is plotted along X-axis and pV along Y-axis, then a straight line parallel to the pressure axis is obtained.

Simple problems related to Boyle’s law:

The volume of air bubbles increases as they ascend in water. As the bubbles are rising up, the surrounding liquid exerts lesser pressure on the bubbles.

According to Boyle’s law, with a decrease in pressure, their volume will increase. Here the temperature is considered constant.

When a balloon is filled with gas both its volume and pressure increase. But in that case, Boyle’s law is not violated, since the mass of the gas filled in the balloon (does not remain the same) increases.

At higher altitudes, the atmospheric pressure is low and the air is less dense. As a result, for breathing less oxygen becomes available.

So mountaineers have to carry oxygen cylinders for breathing while climbing the mountain.

WBBSE Chapter 2 Behaviour Of Gases Simple Numerical Problems

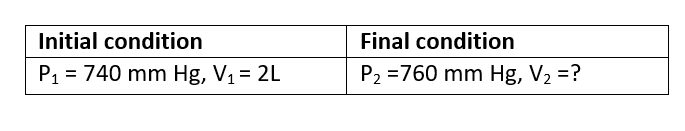

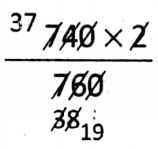

Question 1. At room temperature and 740 mm Hg pressure, the volume of a certain mass of a gas is 2L. At the same temperature, what will be its volume at 760 mm Hg?

Answer:

Given:

At constant temperature, according to Boyle’s law: P1V1 = P2V2 So that 740 x 2 = 760 x V2 ⇒ V2 =

⇒ \(\frac{37}{19}=1.94 \mathrm{~L}\)

Wbbse Class 10 Physical Science Solutions

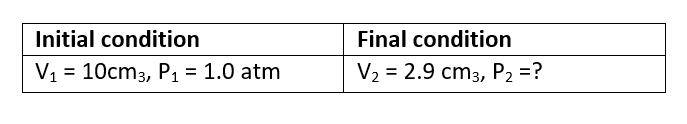

Question 2. A syringe has a volume of 10 cm³ at a pressure of 1.0 atm. Its plunger is pushed down to change the volume to 2.9 cm3 at the same temperature. What will be the final pressure?

Answer: Given:

At constant temperature, according to Boyle’s law: P1V1 = P2V2

So that, 1.0 x 10 = P2 x 2.9 \(\Rightarrow p_2=\frac{10}{2 \cdot 9}=\frac{100}{29}=3 \cdot 44 \text { atm }\)

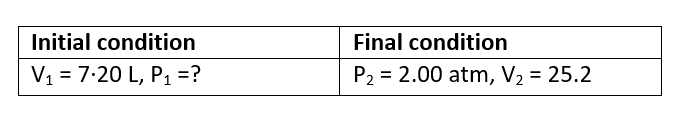

Question 3. A balloon contains 7-20 L of He. Its pressure is reduced to 2-00 atm and the balloon expands to occupy a volume of 25-2 L.

What was the initial pressure exerted on the balloon? (Assume that temperature remains constant throughout)

Answer: Given:

At constant temperature, according to Boyle’s law: P1V1 = P2V2

So that p1 × 7.20 = 2.00 x 25.2 \(\Rightarrow \quad p_1=\frac{2.00 \times 25 \cdot 2}{7 \cdot 20}\)

=7. 00 am

WBBSE Chapter 2 Behaviour Of Gases Charles’ Law

In 1787 French scientist Jacques Charles investigated the effect of a change in temperature on the volume of a fixed mass of gas keeping pressure constant, According to him, as the temperature of the gas increases its volume increases and as temperature decreases volume decreases. Why?

Because as you heat up a gas, the gas molecules move faster K.E. increases and they take up more space (volume).

This is possible only if pressure is kept constant. Similarly, we can explain the vice-versa case. Based on such observations, he discovered a gas law that is known as Charles’ law.

Charles’ law: At constant pressure, the volume of a fixed mass of gas increases or decreases by \(\frac{1}{273}\) times the volume of the gas at 0°C for every 1°C rise or fall in temperature.

Here \(\frac{1}{273}\) is called the coefficient of volume expansion. Its value is the same for all gases.

Explanation of Charles’ law: Suppose at 0°C temperature, the volume of a given mass of gas at constant pressure be Vo.

Keeping pressure fixed, if the temperature is increased by 1°C, then volume increases by \(\frac{V_0}{273}\)

Therefore, the volume of the gas at 1°C is V1= Original volume + Increase in volume + increase in volume = \(V_0+\frac{V_0}{273}\)=\(V_0\left(1+\frac{1}{273}\right)\)

At the same pressure, the volume of the gas for a 2°C rise in temperature is \(V_2=V_0\left(1+\frac{2}{273}\right)\)

Similarly, the volume of the gas at t°C is \(V_t\) = \(V_0\left(1+\frac{t}{273}\right)\)

Again, at the same pressure, for lowering in temperature by 1°C (i.e. at 1°C temperature), the volume of the gas decreases to \(V_{-1}=V_0\left(1-\frac{1}{273}\right)\)

Hence, the volume of the gas at t°C is \(V_{-1}=V_0\left(1-\frac{t}{273}\right)\)

Graphical representation of Charles’ law (V vs t (At constant pressure) graph): If a graph is plotted for Charles’ law, take the V vs t graph.

Along the y-axis and t (in °C) along the x-axis, we get a straight line. Here we see that volume is directly proportional to temperature, i.e, as temperature increases, volume increases and vice-versa.

Now, if we extend the graph backwards, the line meets the temperature axis at -273°C.

Theoretically, it means that at -273°C temperature, all gases occupy zero volume, according to Charles.

Scientist Kelvin named this temperature absolute zero temperature. Because -273°C is the lowest possible temperature in the universe.

The accurate value of this temperature is -273-15°C. In reality, before reaching -273°C temperature, all gases convert into liquids.

(Charles’ law is not applicable for liquid). This type of graph at constant pressure is called isobar (iso = same, bar = pressure).

WBBSE Chapter 2 Behaviour Of Gases Absolute Scale Of Temperature

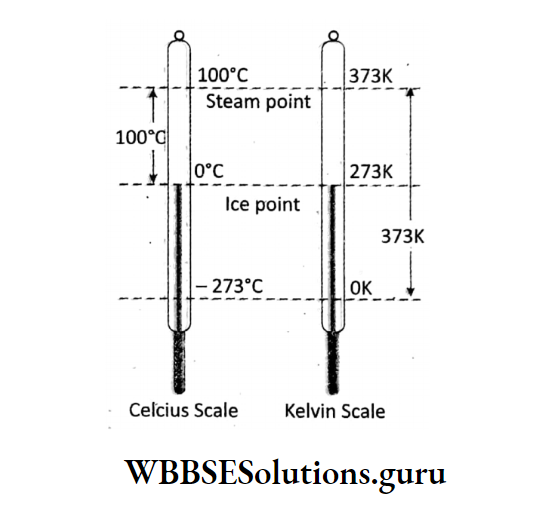

Kelvin observed that at constant pressure, the V-t graph for different gases is a straight line and all lines meet the temperature axis at 273°C.

Thus, -273°C is such a temperature which does not depend on the properties of the gas.

Using this concept, Kelvin developed a new scale of temperature which has its zero point (0) at -273°C, and the scale is called the absolute scale of temperature or Kelvin scale.

In this scale, the temperature reading is denoted by K unit, the temperature by T (absolute temperature) and each degree is taken equal to a degree in Celsius scale.

By definition: OK = -273°C and 1°C = 1K. Adding 273 with the Celsius scale reading, we can get the absolute scale reading.

A temperature t°C in Celsius scale will be in absolute scale: TK = (t + 273)°C.

The freezing point of water (0°C) in absolute scale is 273 K and the steam point of water (100°C) is 373 K. The value of absolute zero (OK) Celcius Scale in Fahrenheit scale is – 459-4°F.

Note:

- Absolute temperature is independent of the properties of the gas.

- In this scale, a temperature may be zero or positive, no negative absolute temperature is possible.

WBBSE Chapter 2 Behaviour Of Gases Representation Of Charles’ Law In Terms Of Absolute Temperature

Suppose at constant pressure a fixed mass of gas has volume V0 at 0°C, V1 at t1 °C and V2 at t2 °C.

According to Charles’ law: \(V_1=V_0\left(1+\frac{t_1}{273}\right)\)=\(V_0\left(\frac{273+t_1}{273}\right)=V_0 \cdot \frac{T_1}{273}\)

[Where T1 is absolute value of t°C i.e. T1 K = (t + 273)°C]

Similarly, \(V_2=V_0 \cdot \frac{T_2}{273} .\)

2. where T2 K=(t2+273)°C

Dividing 1 or 2: \( \) or,\(\frac{V_1}{V_2}=\frac{T_1}{T_2} \text { or, } \frac{V_1}{T_1}=\frac{V_2}{T_2}\)

Thus, the ratio of volume and absolute temperature for a given mass of gas is constant, provided pressure is kept constant.

So, Charles’ law can be used to relate initial and final conditions.

= constant or, \(\frac{V}{T}\) at constant pressure.

Hence, we arrived at the alternate statement of Charles’ law At constant pressure, for a fixed mass of gas, the volume of gas is directly proportional to its absolute temperature.

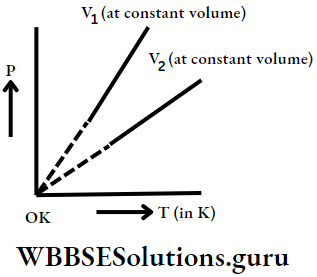

V vs T (in K) graph: As the temperature at const. press p1 increases the volume of gas increases and vice-versa.

So the V-T graph is a straight line. How far can this volume decrease?

When the gas reached absolute zero temperature (-273°C or OK), its volume becomes zero (but in reality, this is not possible).

Simple non-numerical problem related to Charles’ law: In Diwali, when you light up a sky lantern or air balloon, the volume of air inside it increases.

(As temperature increases, the volume also increases). As a result, the density decreases. This makes the balloon lighter than its surrounding air.

Hence, a buoyant force acts on the balloon in an upward direction which helps the balloon to rise into the air.

WBBSE Chapter 2 Behaviour Of Gases Simple Numerical Problems

Remember In Charles’ law, whenever we talk about temperature we always use the absolute value. But units of pressure and volume can be different.

Wbbse Class 10 Physical Science Solutions

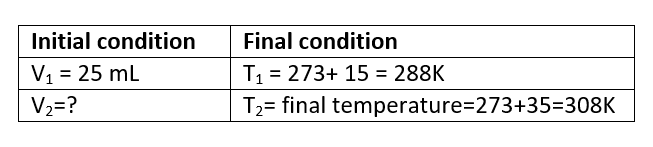

Question 1. A balloon is filled with 25 mL H2 gas at 15°C. The balloon is taken to a high altitude where pressure remains constant, the temperature becomes 35°C. Find the volume of the balloon.

Answer:

∴ Pressure remains constant. According to Charles’ law:

⇒ \(\frac{V_1}{T_1}=\frac{V_2}{T_2}\)

Given:

So that \(V_2=\frac{V_1 \times T_2}{T_1}\)=\(\frac{25 \times 308}{288} \mathrm{~mL}=26.74 \mathrm{~mL}\)

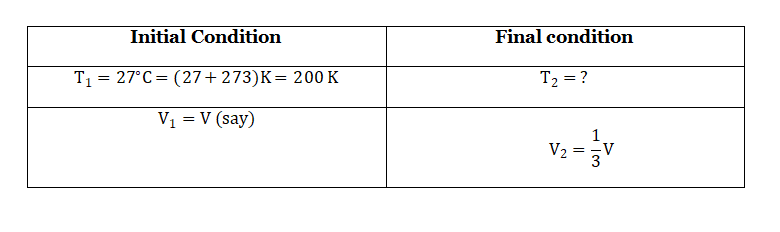

Question 2. To what temperature must a gas at 27°C be cooled in order to reduce its volume to one-third of the original volume keeping the pressure constant?

Answer:

Given:

At constant pressure, according to Charles’ law: \(\frac{V_1}{T_1}=\frac{V_2}{T_2}\)

So that

⇒T2 =100 K=(100-273)°C=-173°C.

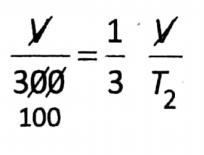

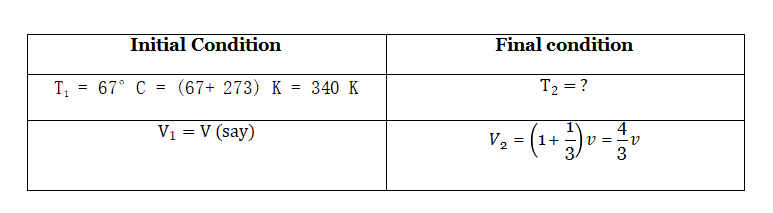

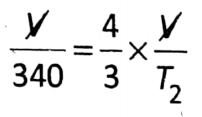

Question 3. In a glass, vessel air is kept at a temperature of 67°C. Keeping pressure the same, the temperature is increased. At what temperature, one-third air will go out of the vessel?

Answer:

Given:

At constant pressure, according to Charles’ law: \(\frac{V_1}{T_1}=\frac{V_2}{T_2}\)

So that,

⇒ \(T_2=\frac{4 \times 340}{3}=\frac{1360}{3}\)= 453-K (453.3-273)°C 180.3°C

WBBSE Chapter 2 Behaviour Of Gases The Combined Form Of Boyle’s And Charles’ Laws

Suppose for a fixed mass of gas the pressure, volume and absolute temperature are p, V and T respectively.

According to Boyle’s law: \( V \propto \frac{1}{p}\)

According to Charles’ law: \(V \propto T\) Combining these two relations:

⇒ \(V \propto \frac{T}{p}\) when both T and p vary

⇒ \(V=\frac{k T}{p} \Rightarrow \mathrm{PV}=k T\)…..1. So that, \(\frac{p V}{T}=k\)(constant)….2

Where k is a constant whose value depends on the units of p, V, T and the mass of the gas. The equation is obtained by combining Boyle’s and Charles’ laws into a single expression.

The equation pV=kT is called the mathematical form of combined gas law. This equation is also called the equation of state of an ideal gas because the physical property of an ideal gas depends on its pressure, volume and temperature.

The equation shows that for a given quantity gas how p, V and T affect each other when all the three parameters vary for initial and final conditions.

Thus from the equation, we can write for the initial condition \(\frac{p_1 V_1}{T_1}=k\) and for the final condition \(\frac{p_2 V_2}{T_2}=k.\)

WBBSE Chapter 2 Behaviour Of Gases Simple Numerical Problems

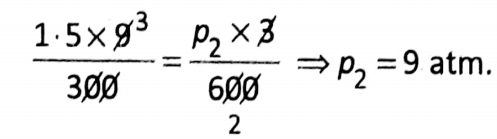

Question 1. At 27°C a sample of N2 gas is placed in a flexible 9-0 L container at a pressure of 1.5 atm. The container is compressed to a volume of 3.0 L and the gas is heated up to 327°C. Then what will be the new pressure inside the container?

Answer:

Given:

From combined gas law: \(\frac{p_1 V_1}{T_1}=\frac{p_2 V_2}{T_2}\)

So that,

Wbbse Class 10 Physical Science Solutions

Question 2. A definite amount of CO2 gas occupies a volume of 512 cm³ at STP. Find its volume at 17°C and 750 mm of Hg.

Answer:

P1 = 760 mm of Hg; T1 = 273 +0 = 273K; V1=1.5dm3

P2 = 750 mm of Hg; T2 = 273 +17= 290K; V2 =?

Gas equation is ,\(\frac{p_1 V_1}{T_1}=\frac{p_2 V_2}{T_2}\)

So that \(\frac{760 \times 512}{273}=\frac{750 \times V_2}{290}\)\(\Rightarrow V_2=\frac{760 \times 512 \times 290}{273 \times 750} \mathrm{~cm}^3=551.13 \mathrm{~cm}^3\)

Wbbse Physical Science Class 10

Question 3. In the laboratory 1.5 dm3 of dry H2 gas was prepared at a pressure of 750 mm Hg and temperature of 27°C. Find the volume of the gas at 17°C and 760 mm of Hg.

Answer:

According to the gas equation \(\frac{p_1 V_1}{T_1}=\frac{p_2 V_2}{T_2}\)

P1 = 750 mm of Hg; T1 = 273 +27= 300K; V1 = 1.5 dm3

P2 = 760 mm of Hg; T2 = 273 +17= 290K; V2 =?

So that \(\frac{760 \times 512}{273}=\frac{750 \times V_2}{290}\) \(\Rightarrow V_2=\frac{760 \times 512 \times 290}{273 \times 750} \mathrm{~cm}^3=551.13 \mathrm{~cm}^3\)

WBBSE Chapter 2 Behaviour Of Gases Ideal gas

The gases which obey the equation of state of an ideal gas “pV = kr” at all pressures and temperatures are called ideal gases.

But in real situations, no ideal gas can exist. All gases in the universe like O2, N2, H2, CO2, etc. are non-ideal or real gases.

Some real gases behave like ideal gases under certain conditions. Let’s discuss the conditions: We know that gases are affected by pressure and temperature.

From the equation \(p V=k T, V=\frac{k T}{p}\). At constant temperature,

⇒ \(V \propto \frac{1}{p}\)(Boyle’s law) So, keeping the temperature constant, at very high pressure (suppose p→ ∞), V→ O.

In reality, at very high pressure, gases change into liquids. So, the relation pV = kT is not applicable for real gases at very high pressure.

On the other hand, from pV = kT, we can say that at constant pressure, V∞ T (Charles’ law).

In reality, as temperature decreases volume also decreases, but before reaching an OK temperature, gases convert into liquids.

So, the relation pV = kT does not hold well for real gases at very low temperatures.

For example, at high temperatures and low pressure, molecules of real gases move far away from each other (at the maximum possible distance).

In contrast, at low temperatures and high pressure, molecules of real gases come close to each other.

Therefore we can say that at very high temperatures and very low pressures, a real gas behaves like an ideal gas.

Hence, the gases, which do not obey the equation “pV = kT” except at very high temperatures and very low pressures are called real gases.

A natural question arises: Why do we study ideal gas? Although the concept of ideality is an abstraction, to estimate p, V and T of any real gas, the relation pV=KT is undoubtedly a very useful idea under certain conditions.

WBBSE Chapter 2 Behaviour Of Gases Avogadro’s law

At constant temperature and pressure, the volume occupied by 1 mol of any gas is called its molar volume (1 mol = 6.02 x1023 no. of molecules).

If the mol of a gas has a volume of V then the molar volume will be\(\frac{v}{n}\). Due to changes in temperature and pressure, the volume of gas changes so molar volume also changes.

Experimental results show that molar volumes \(\left(\frac{v}{n}\right)\) for different real gases are approximately the same, i.e., \(\left(\frac{v}{n}\right)\) are independent of the nature of the gas, provided temperature and pressure remain the same.

At standard temperature and pressure (STP), the molar volume of all real gases is found to be nearly equal and its limiting value is (22.4 L) or 22400 mL.

This volume (22-4 L) is called the molar volume at STP. Thus, at STP, 1 mol of H2, N2, CO2, O2 … occupies a volume equal to 22.4 L.

Based on these experimental results, in 1811 Italian chemist Amedio Avogadro discovered a law relating the volume of gas to the number of mol or molecules which is known as Avogadro’s law or Avogadro’s hypothesis.

Avogadro’s law: Under similar conditions of temperature and pressure, an equal volume of all gases contains an equal number of molecules.

Explanation of Avogadro’s law: Suppose we have a container of volume 100 mL filled with H2 gas and the no. of molecules in it is x at a given T and p.

If H2 is replaced by another gas say N2 then under the same T and p, the no. of molecules will be x. Under similar conditions, 100 mL of all other gases like O2, NH3, CH4, SO2…. will have x no. of molecules.

So 200 mL of CO contains 2x molecules, 150 mL NO2 contains \(\frac{3}{2} x\) molecules, 300 mL NH3 contains 3x molecules, 50 mL H2 contains molecules, etc.

According to Avogadro’s law, we can say that under similar conditions of temperature and pressure, the volume of a gas is directly proportional to the no. of molecules present in it.

Mathematically, V∞on where V = volume, n = no. of mol. Therefore \(\frac{v}{n}=k\)(constant).

During Avogadro’s time, the concept of atoms and molecules was purely hypothetical. Avogadro first explained the distinction between these two in his molecular theory.

According to him, the smallest particles of gases which can exist independently are molecules, not atoms.

In this context, it is important to mention that in Avogadro’s law ‘volume’ means the volume occupied by the gas- not the volume of gas molecules.

For example, at STP volume of 1 mol or 6-023 x 1023 molecules of a gas is very much negligible as compared to 22.4 L.

Now let us take the reaction: H2+ Cl2 → HCI.

Here, 1 volume of H2 combines with 1 volume of Cl2 to form 2 volumes of HCI. According to Avogadro’s law,

1 molecule of H2 + 1 molecule of Cl2 → 2 molecules of HCI

⇒ \(\frac{1}{2}\) molecule of H2 +\(\frac{1}{2}\) molecule of Cl2 → 1 molecule of HCI

An atom is an individual. A group of atoms are called a molecule. That is,

H-atom + H-atom → 1 H2 molecule⇒ 1 H-atom → ½H2 molecule, according to Dalton’s atomic theory, this can exist and this concept was valid.

Gay-Lussac’s law of combining volumes: When gases react together to form gaseous products under similar conditions of temperature and pressure, then the ratio between volumes of reactant gases and product will always be in simple whole numbers.

Explanation of Gay-Lussac’s law using Avogadro’s law: This law is applicable only to the reaction of gases.

Let at the same temperature and pressure molecules of A gas combine with ‘b’ molecules of B gas to form ‘c’ molecules of C gas.

where a, b, and c are simple whole numbers. According to Avogadro’s law, at the same temperature and pressure equal volumes (V) of all gases contain an equal number of molecules (n).

Then, volume of ‘a’ molecules of A gas = \(\frac{\mathrm{V} \times a}{n}\)

the volume of ‘b’ molecules of B gas = \(=\frac{V \times b}{n}\)

and volume of ‘c’ molecules of C gas =\(\frac{\mathrm{V} \times c}{n}\)

The ratio of the volumes is at the same temperature and pressure =

⇒ \(\frac{\vee \times a}{n}: \frac{\vee \times b}{n}: \frac{\vee \times c}{n}\) = a: b: c.

The ratio is simple [as a, b, and c are whole simple numbers. This is Gay-Lussac’s law.]

Moist air is less dense than dry air: Dry air contains 78% N2, 21% O2 and the remaining 1% trace gases, whereas moist air contains N2, O2 and H2O (water vapour).

Molar mass of N2, O2 and H2O are respectively 28 g.mol-1, 32 g.mol-1 and 18 g.mol-1.

That is H2O is relatively less dense than N2 and O2. According to Avogadro’s law, we know that equal volumes of all gases under the same conditions of temperature and pressure contain equal no. of molecules.

This can be understood easily with the help of imagining a container of volume V containing dry air at a certain T and p.

Imagine there are 6 molecules of N2 and 9 molecules of O2, then the total gram molecular mass would be = 28 × 6 +32 × 9456 g.

If water vapor molecules are allowed to introduce in the same container then heavier N2 or O2 molecules must leave so that the total no. of molecules remains the same.

There are 5 molecules of N2 7 molecules of O2 and 3 molecules of H2O, then the total gram molecular mass of moist air becomes 28 × 5 + 32 × 7 + 18 × 3 = 418 g.

WBBSE Chapter 2 Behaviour Of Gases Combination Of Boyle’s, Charles’ And Avogadro’s Law Ideal Gas Equation

Suppose at pressure p and absolute temperature 7 the volume of nmol of gas is V. (when n and T remain constant)

According to Boyle’s law: \(V \propto \frac{1}{p}\) (when n and p remain constant)

According to Charles’ law: \(V \propto T\) (when T and p remain constant)

According to Avogadro’s law: \(V \propto n\) (when T and p remain constant)

Combines these three relations when p, T and n are variables \(V \propto \frac{n T}{p} \Rightarrow V=\frac{n R T}{p}\) where ‘R’ is a constant.

Putting n = 1 in the equation, we get R.

So for 1 mol of any gas, the value of R is equal and the value does not depend on the nature of the gas.

By this logic, ‘R’ is called the molar gas constant or universal gas constant.

In the equation, there is no such parameter which depends on the nature of the gas. By this logic, equation P is called the equation of state for n mol of an ideal gas or simply the ideal gas equation.

p-T graph: From the equation \(p=\frac{n R T}{V}\) we can write p= Keeping mass no. of mol (n) and volume (v) V unchanged we see that p∞ Tp = kT (k → being a proportionality constant)

⇒ \(\Rightarrow \frac{p}{T}=k \Rightarrow \frac{p_1}{T_1}=\frac{p_2}{T_2} .\)

If a graph is plotted taking absolute temp (T) along the x-axis and pressure (p) along the y-axis, we will get a straight line Extending the line backwards, it meets the temperature axis at OK (or -273°C) temperature.

Theoretically, at temp OK, the pressure of gas becomes equal to zero (but in reality, this is not possible).

Representation of equation pV = nRT as pV= \(\left(\frac{\mathbf{W}}{\mathbf{M}}\right)\) Suppose the mass of n mol of an ideal gas is W g. If its molar mass is M g.mol-1, then no. of moles, \(n=\frac{W}{M}=\frac{\text { Given mass }}{\text { Molar mass (in gram) }}\) So, from the ideal gas equation, we can write, \(p V=n R T \Rightarrow p V=\left(\frac{W}{M}\right)\)

Note: M is the molar mass (unit: g.mol-1)-not the molecular weight (which is a dimensional quantity).

Unit of ‘R’ from dimensional analysis of ideal gas equation: From ideal gas equation pV=nRT we get \(\mathrm{R}=\frac{p \mathrm{~V}}{n T}\) Remember, ‘T’ is always expressed in Kelvin (K) so for simplicity we can write \(R=\frac{p V}{n T(i n K)}\)

⇒ \([\mathrm{R}]=\frac{[p][\mathrm{V}]}{[n][\mathrm{K}]}=\frac{[\mathrm{F} / \mathrm{A}][\mathrm{V}]}{[n][\mathrm{K}]}=\frac{\left[\frac{\mathrm{MLT}^{-2}}{\mathrm{~L}^2}\right]\left[\mathrm{L}^3\right]}{[n][\mathrm{K}]}=\frac{\left[\mathrm{ML}^2 \mathrm{~T}^{-2}\right]}{[n][\mathrm{K}]}=\frac{[\mathrm{W}]}{[n][\mathrm{K}]}\)

Here unit of [W]= work done or energy is J.mol-1. K-1 and CGS unit erg. Mol-1. K-1. different in different systems.

So SI unit of ‘R’ Similar unit is cal.mol-1, K1. These units are mainly used for energy calculations. The most commonly used unit of ‘R’ is atm. litre/mol. K.

We know that 1 mol of an ideal gas occupies a volume of 22.4 L at STP (at temperature T = 273 K and pressure = 1 atm). Then the value of ‘R’ is found to be

⇒ \(R=\frac{1 \mathrm{~atm} \times 22.4 \mathrm{~L}}{1 \mathrm{~mol} \times 273 \mathrm{~K}}=0.082 \mathrm{~atm} \text {.litre } / \mathrm{mol} . \mathrm{K} \text {. }\)

Another value: R = 8.31 J.mol-1.K-1 8.31 x 107 erg. mol-1.K-12 cal. mol-1, K-1

WBBSE Chapter 2 Behaviour Of Gases Simple Numerical Problems

Wbbse Physical Science Class 10

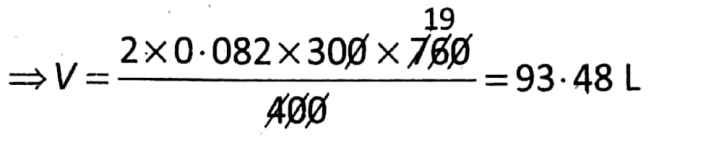

Question 1. Find the volume of 32 g of methane at 27°C and 400 mm Hg.

Answer:

Given: \(n=\frac{W}{M}=\frac{\text { Given mass }}{\text { Molar mass }}=\frac{32 g}{(12+4) g}=2\)

T = 27°C = (27 + 273) K = 300 K.

p = 400 mm Hg= \(\frac{400}{760} \mathrm{~atm}\)

V =?

We know that pV = nRT

So that \(\frac{400}{760}\) V =2 x 0.082 x 300

Wbbse Physical Science Class 10

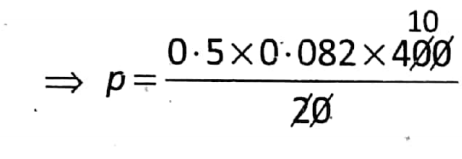

Question 2. Find the pressure (in mm Hg unit) exerted by 14 g of N2 at 127°C kept in a container of volume 20L.

Answer:

Given: \(n=\frac{W}{M}=\frac{14}{14 \times 2}=0.5\)

T= 127°C=(127+273) K = 400 K

V=30L

p=?

We know that Pv=Nrt

So that p×30=0.5×0.082×400

WBBSE Chapter 2 Behaviour Of Gases The Behaviour Of Ideal Gas The Molecular Level

We know that no real gas is ideal, but some real gases behave like ideal gas under certain conditions.

Although they have some common properties like high compressibility, expansibility, and diffusion. In the 18th century Boltzmann, Clausius, and Maxwell put forward a model applicable to all gases.

This is known as the kinetic theory of gases and is applicable to ideal gases only. Some important postulates (or assumptions) of the kinetic theory of gases are:

Gases are made up of very tiny particles called molecules (or atoms). Molecules of the same gas are identical in all respects (mass, shape, size).

The gas molecules are moving randomly in all possible directions with all possible speeds ranging from zero to infinity.

During such chaotic motion, molecules collide against each other and with the wall of the container. This gives rise to gaseous pressure exerted on the wall.

All collisions of gas molecules among themselves and with the wall of the container are elastic in nature (which means no loss in momentum and K.E.).

The K.E. of a gas depends only upon (absolute) temperature -not upon the nature of the gas. It has been established that the temperature of a gas is directly proportional to the average K.E. of its molecules.

Note that, it is not possible to determine the speed or K.E. of a single molecule at any particular instant.